By Andrew Osmond.

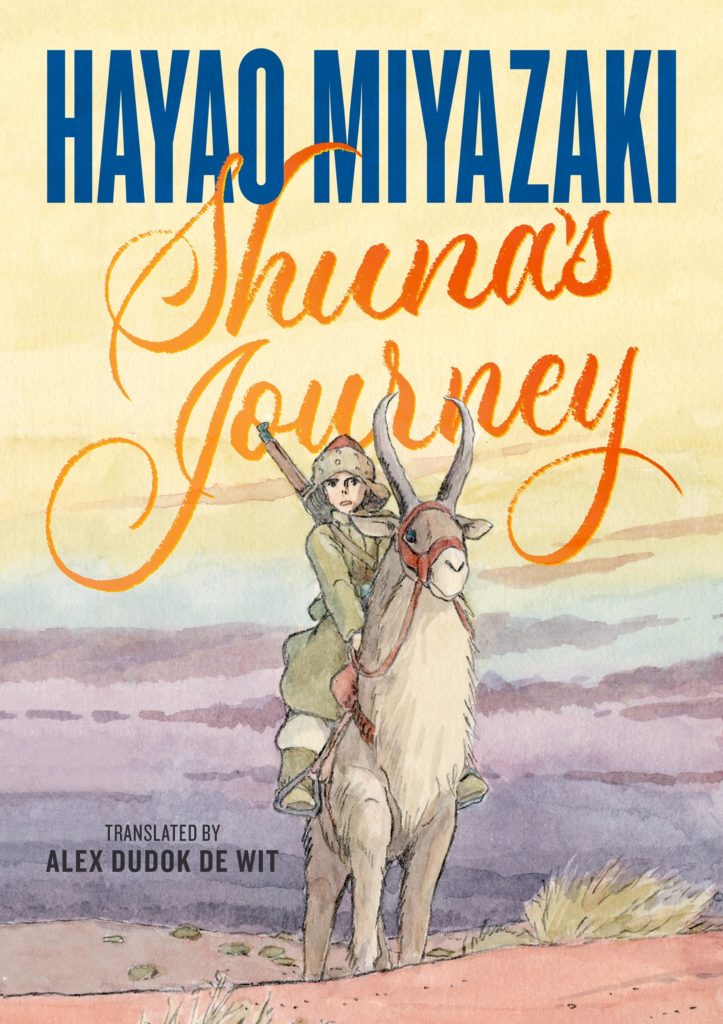

In the last twelve months, we’ve had the first ever English-language releases of two vintage Miyazaki works, both forty years old or more. The first is his 1978 TV series Future Boy Conan, which I wrote up here. The second is his 1982 manga (kind of), Shuna’s Journey, which is now available in a splendid new translation from the animation critic and journalist Alex Dudok de Wit.

I say Shuna’s Journey is a kind of manga, because it’s very different from the norm. It’s in colour, all 144 pages of it, full of soft, atmospheric watercolours. Miyazaki says he hates the idea of people watching his films over and over, but surely he made this book hoping kids would leaf back and forth, from desolate rust-coloured plains, down deadly grey cliffs into emerald wonderlands, and then home to green pastures. But it’s not cosy bedtime reading – the content is Princess Mononoke level.

The book doesn’t use many speech bubbles, favouring third-person narration. Some of the translated text has a Tolkienish ring. “Sad and impoverished were their lives,” reads one of the first captions. “Beautiful and brutal was the nature they lived in.” Miyazaki is describing the home kingdom of the hero Shuna; we see hive-like stone houses in a deep valley. Rather than the “homes” in Nausicaa or Mononoke, it feels like Laputa’s village, suggesting Miyazaki’s vision of that town was largely in place before he visited Wales in 1985.

Shuna’s kingdom is in a grim state, where people work themselves into the ground for meagre harvests. Then Shuna – the androgynous young prince of the valley, who looks extremely like Miyazaki’s Nausicaa – comes across a dying traveller from the outside world. The stranger is quickly established as an aged “double” of Shuna. He was a prince of an impoverished country too, who also met a traveller in his youth. This first traveller carried huge seeds, now dead, but supposedly from a marvellous land where such seeds grow into crops that “swayed into waves of fertility,” ending hunger and war.

The man Shuna saved was consumed by the search, dying in a couple of pages. Nonetheless, his story has already infected Shuna, who gazes out at the horizon. Miyazaki disparages Hollywood, but readers will find it hard to look at the relevant frame in Shuna and not think of Luke Skywalker, looking out at a twin sunset.

In a new essay in the book, Dudok de Wit highlights how Shuna is unlike most Miyazaki characters. He starts his journey in defiance of the people who love him and beg him to stay. “Under a new moon,” Miyazaki writes, “Shuna broke the law of the kingdom and saddled his Yakkul.” And yes, the Yakkul in question is a tame elk which looks exactly like its namesake in Princess Mononoke.

Shuna’s early pages often feel like a remix of that film and Miyazaki’s Nausicaa, especially the manga version. But as the tale proceeds, it develops its own identity, though it often echoes other works. The lands Shuna discovers evoke the Rene Laloux cartoon, Fantastic Planet. But they also have shades of the horror of H.P. Lovecraft – these are realms more inscrutable than those of the Shishi-gami, and deadlier. But the images also anticipate fantasy media to come. One of the strangest images, involving a moonlike vessel disgorging bodies, has shades of Jordan Peele’s film Nope.

The book includes Miyazaki’s translated Afterword from 1983 and Dudok de Wit’s essay, which set Shuna in context. It was part of a crucial phase in Miyazaki’s career. He was in his early forties, with magnificent work behind him, but still with so many impossible-seeming dreams. Shuna was a compromise – he’d wanted to make it as a film, but, he said, “a project as unglamorous as this would not go far in Japan’s current climate.” Perhaps he was cynical; 1983 was the year of the harrowing Barefoot Gen.

As Dudok de Wit says, Miyazaki was exploring a “jumble of ideas,” as illustrated in the back pages of the art book Nausicaa: Water Colour Impressions. They show knights, dragons, flying castles, goblins in armour. Miyazaki’s well-known influences range from the Earthsea books by Ursula Le Guin to the fantasy comic Rowlf by Richard Corben; he tried and failed to adapt both. Looking at Shuna, you may wonder if it was also informed by the fantasy comics of France’s Jean Giraud (“Moebius”). In one talk, Miyazaki mentioned he’d read Moebius’ strip Arzach in 1980, which “shocked” him. However, Miyazaki also says he had a “consolidated style” by then and couldn’t take lessons from Moebius’ art.

Shuna’s acknowledged basis is a Tibetan folktale, which also has a prince seeking seeds. However, as Dudok de Wit explains, Miyazaki changed the tale considerably. The last section of Shuna could be influenced by Nausicaa – not Miyazaki’s character Nausicaa, but the Nausicaa of Greek mythology, and the saviour role she plays in the legend of Odysseus. Moreover, Shuna’s final pages involve a cunning trick – Yakkul is involved – that parallels the end of the story of Odysseus, minus the bloodbath.

As for how Shuna resonates within Miyazaki’s own work, that could take up a whole other article. Miyazaki reportedly started Shuna in 1980, but he was probably still working on it while he was also drawing the early Nausicaa chapters in Animage magazine. Consequently, it’s often hard to say which of their shared ingredients “originated” in Shuna as opposed to Nausicaa. However, Shuna’s scenes and images definitely leak into Princess Mononoke (a campfire conversation), and also Goro Miyazaki’s Tales from Earthsea (a beached ship, a slavers’ wagon.)

I also suspect Shuna is also referenced in a non-Miyazaki anime, Makoto Shinkai’sChildren Who Chase Lost Voices From Deep Below. The whole of that film is Miyazaki-ish, but the climactic scenes involve a perilous climb down a towering cliff, very like a sequence in Shuna. Shinkai’s film also involves a man who’s pathologically obsessed with completing his journey, much like Shuna.

The second point is probably coincidence, but it draws attention to a changeover in Miyazaki’s stories, where Shuna may be the hinge. Through Miyazaki’s work, there’s often a “lost soul” character, who’s lost their spiritual bearings and needs someone else’s support for their redemption. That figure can be a woman, as with Monsley in Future Boy Conan, Kushana in Nausicaa (in the manga especially) and Eboshi in Princess Mononoke. The motif itself seemingly comes from an earlier character, Hilda in The Adventure of Hols. Miyazaki worked on that film, but he stressed that Hilda was the creation of Hols’ director, Isao Takahata.

However, in many of Miyazaki’s later works, the “lost soul” character is male. Think of Porco in Porco Rosso, Haku in Spirited Away, Howl in Howl’s Moving Castle and Jiro in The Wind Rises. All these characters need a woman or girl to lift and sustain them, like Naoko in Wind Rises, holding her husband’s hand as Jiro is carried off by dreams of planes. It’s impossible not to think this reflects Miyazaki’s life, and what he gave up for his obsessions. To quote the title of one of his Starting Point essays, “I Left the Raising of Our Children To My Wife.”

Either way, Shuna may be Miyazaki’s first “lost” male character, predating all the others in this paragraph. Like Haku in Spirited Away, he needs a girl’s voice to lead him back to the light.

Shuna suggests many analogies, but there’s also one huge contrast. As mentioned above, Shuna was created while Miyazaki was also writing the early chapters of the Nausicaa manga. In Japan, Shuna was published in 1983, just as Miyazaki moved onto the Nausicaa film and suspended work on the strip. Many of Shuna’s buyers were surely Nausicaa fans looking for a stopgap.

Looking at Shuna and the Nausicaa manga side by side, you can see they’re by the same hand, and yet they’re so very different. Like the huge majority of manga, Nausicaa is black-and-white. Also, as many fans have pointed out, it’s dense, with intricate details and shading, and sometimes ten panels to one page.

True, it was serialised in Animage, an oversized magazine with bigger pages than most manga magazines and many of Nausicaa’s own reprints (especially the “Perfect Collection” in America, which scrunched the pictures ruthlessly). Still, even in the larger formats, the pictures are often not instantly decipherable – especially parts of battles. Some readers find the manga a terrible chore to get through. The Mangasplaining podcast is especially scathing on the subject.

For those readers, Shuna is a precision-targeted antidote to Nausicaa. Its colour pictures are instantly legible, and far larger, with many pictures filling a whole page or a double-page spread. They’re much closer to the watercolour art that Miyazaki painted, often under protest, to promote the Nausicaa manga (example).

In one scene, Shuna’s riding Yakkul and attacking a slavers’ wagon – it’s reminiscent of Hollywood Westerns. Miyazaki chooses to depict this through a single double-page action spread, whereas similar action scenes in Nausicaa could easily take five pages and dozens of panels. You can look at the Shuna spread for a moment if you want, and then speed on, but it’s being drawn for when you look back at the picture, for the second or fifth or tenth time.

The pictures still have small details to hook onto, like the beads that adorn Shuna’s headwear in umpteen frames, like Nausicaa’s flight goggles. But the book still feels far looser and softer than Nausicaa, partly because Shuna’s costumes are all simple-looking cloth, whereas Nausicaa has many scenes of knights in armour. Shuna’s colour lets you feel the light and textures – for example, the damp, louring clouds behind the hero as he descends a massive cliff to the Land of the God-Folk.

Miyazaki would go on to draw many short strips with these qualities, such as the source strip for Porco Rosso. But, to my knowledge, he’s never drawn another book with the style and accessibility of Shuna, and that’s a shame. It’s a terrific work, and this new edition does it full justice. By the way, the rave quotes on the back cover come from familiar names. One is director Guillermo Del Toro, sometimes nicknamed “Totoro-san.” The other is actress Daisy Ridley, whose Star Wars character Rey is frequently placed by fans on the same continuum as Nausicaa and Shuna.

Andrew Osmond is the author of 100 Animated Feature Films. Shuna’s Journey, by Hayao Miyazaki, is available now from St Martin’s Press.