By Andrew Osmond.

March comes in like a lion resists obvious categorisation. You could call it a “slice of life” anime, but that’s a pretty useless heading these days; Wikipedia’s list of such anime covers everything from Azumanga Daioh to A Centaur’s Life via From Up on Poppy Hill.

Pinpointing March more, I’d say it’s on the dial between A Silent Voice, with its serious treatment of emotional pain, and Maison Ikkoku with its domestic warmth, though its comedy is toned down several notches from Ikkoku. It’s about an orphaned, withdrawn 17 year-old boy, Rei, living alone in present-day Tokyo, and his charming friendship with three sisters – one adult, one middle-schooler, and one boisterous infant – in the same neighbourhood. All these characters have suffered tragedy and loss, but the show highlights the continuation of their lives, their forging of new relationships.

So this is a particular kind of slice of life. To complicate matters, March is also what Anime News Network calls a “tournament” series. Rei is a prodigy of shogi, a Japanese relative of chess, and he spends much time facing down combatants on the other side of a board. There’s a riveting early set-piece, flashing between two games that Rei plays years apart in the melting summer heat. In both games, his rival is utterly obsessed with beating him; he’s tragically outmatched by Rei but stubbornly refuses to give in, like the hero of his own Shonen Jump strip.

March’s official director is Akiyuki Shinbo (aka Simbo), Shaft’s most famous creator, though many fans argue that Shinbo is now more of an advert for a style, a house brand, like Stan Lee’s masthead at Marvel Comics. March’s first season also has a credited “series director”, Kenjiro Okada, who served time on several of Shaft’s Monogatari anime. However, Okada’s credit seems to be dropped from March’s second TV season, leaving Shinbo as ostensibly the sole director.

Beyond Shaft, March is also suffused with the consciously cutesy style of female artist Chica Umino, who created the acclaimed source manga for the series. Umino’s earlier hit Honey and Clover, about Tokyo art students, may not be familiar to British viewers, but it enjoyed multiple adaptations in Asia. Umino also designed the characters in Production I.G’s comedy-thriller Eden of the East; Eden’s heroine Saki looks like a younger Akari in March.

Finally, one particularly interesting crossover concerns March’s theme music. Like most TV anime, its opening and closing songs are J-pop – they’re both performed by the vastly popular Bump of Chicken, which also contributed “Hello World” to Blood Blockade Battlefront. But what’s far less usual is that the band was associated with the March manga before the anime series was greenlit. In 2014, Bump of Chicken released an animated music video, using imagery from March, to accompany its anthem “Fighter.” (Reportedly, Umino and the band are mutual fans.) “Fighter” is now the closing song of Shaft’s version, while the band’s opening song, “Answer”, has its own March-themed music video.

There are delicate grace notes sprinkled around – a butterfly on water, a balmy French lullaby on the soundtrack – but the boy seems blankly unmoved. He travels to a shogi hall, where he plays the board game with a middle-aged man, not saying a word. The adult seems kind, even fatherly, but we sense Rei’s burning anger as he plays – why, we don’t know. This isn’t an anime that dollops backstory; it will be several episodes before we learn the boy’s history.

So far, this could be a psycho-thriller like Flowers of Evil. And then, at the episode’s halfway point, it turns a ninety-degree corner. Rei is returning to his empty home when he’s forcibly invited to supper by the sisters – Akari (the adult), Hinata (the schoolgirl) and Momo (the jumping bean child). From the moment they appear, the drawing becomes bouncy, exuberant. We’re introduced to the sisters’ cartoon kitties, who have their own catty dialogue variants on “Feed me!”, while written sound effects waft through the picture.

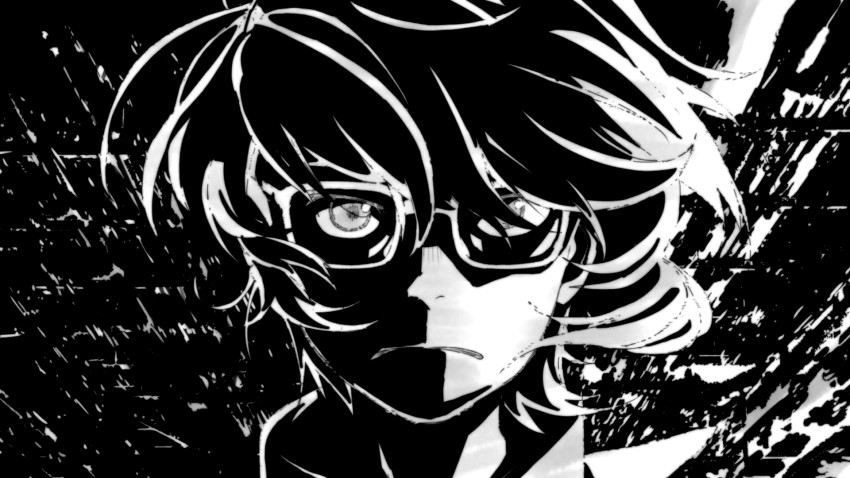

The excess of warmth and cuteness is doubly disorientating. Again, the basic information is withheld at this point – we’re not told at how the sisters know the boy, why they treat him with such affection, or why Rei seems happy with them, literally despite himself. The sisters chase away Rei’s darkness a little, though he daydreams morbidly at the supper table, and when Hinata removes his glasses while he’s sleeping, his eyes are full of tears. Thus we start to build a picture of Rei and his strange life; half numb and solitary, half lit up by the kindness of his surrogate family.

It’s a masterful case of modulated storytelling – Shaft fans may like to compare it to the infamous tonal shifts in Madoka Magica. Later the story opens up. For example, we learn the sisters help their grandpa run a confectionery (wagashi) shop, though the adult Akari also works as a hostess in Tokyo’s Ginza district, which is where she first encountered Rei, zonked out on a pavement. We’re trying to remember any other film or TV show that has a motherly woman gently helping a sozzled lad to vomit, by sticking a finger down his throat… but we’re coming up blank. It’s as emotionally pungent as the show’s understated scenes of grief or depression; Hinata, for example, crying for her mother during Japan’s obon memorial season, looking out over the waterways that pervade the series.

While the series has some of Shaft’s trademark geometric straight lines, overall it has far more gentle freehand drawing, less ostentatious stylisation. There’s a handmade texture to March, an illusion of technical simplicity, despite the graphic sophistication. Rei’s iconic expression is entirely rooted in the graceless downturn of his mouth; supposedly entering adulthood, he looks like a cringing infant. There are frequent visual comparisons of Rei’s depression to water, threatening to drown him; recurring images of rising bubbles aren’t just a motif but punctuation. The extended drowning metaphor may remind viewers of a non-Shaft anime with an oddly similar name – Your Lie in April.

Indeed, when we learn about Rei’s dark backstory, it’s revealed that (small spoiler) one of the story’s lynchpins is a lie that he told, about why he has taken his shogi playing so far. Hint: it’s not because of a youthful love of the sport, like so many other wide-eyed heroes of sports manga. It also turns out that Rei has another surrogate family, and an adoptive “father” who tried to help him, but drove him into deeper darkness at the worst time of his life. Rei being a shogi prodigy only made things worse. As his story unfolds, you may be reminded of real-life cautionary tales like that of the troubled Bobby Fischer, the world’s most famous chess prodigy.

Live-action is one thing, but it’s less usual for anime to cross into real life. It has happened before, though, and especially in the field of sports. Akira correctly called the location of the 2020 Olympics, while Yawara, a manga by Naoki Urasawa about a star judo girl, was running in the 1990s when teenager Ryoko Tamura began her rise to sporting glory. Now March’s portrait of a teenage shogi genius seems to anticipate the miracles wrought in recent years by Sota Fuji, who’s been toppling countless records and champions… and he’s still just 15. Let’s hope he’s happier than March’s Rei, or Bobby Fischer.

Andrew Osmond is the author of 100 Animated Feature Films.

March comes in like a lion is released in the UK by Anime Limited.